|

|

|

|

|

|

Demos for an art audience: Decode:Recode |

|

|

|

by Menace of Spaceballs, Boozoholics and Keyboarders and Axel of Brainstorm

|

Download the pdf here

There has always been a debate in the demoscene; are demos art? Two UK sceners of some proliferance, Smash of Fairlight and EvilPaul of Ate Bit, decided to investigate the matter in a very hands-on-manner, by participating in a museum art-exhibit challenge, which was organized by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. ZINE sat down with the two participants to hear their thoughts on the matter.

"I can't remember if it was EvilPaul who told me about the Decode exhibition at the V&A museum in London, but we went down there together in December 2009 to check it out, and the overwhelming opinion we had about the pieces was 'we could do this.. maybe even better'. Later, around February, Paul sent me the link to this online competition thing - Decode:Recode - where you download this guy's code and edit it a bit, then send it back. He had seen it advertised on the London underground. We both decided we could do better and both decided we didn't want to touch the processing code of the original so decided to ignore the rules and just do something from scratch." EvilPaul adds: "Yeah, they had an animated advert that I saw on my tube journey every morning. After weeks of looking at it I eventually thought we should visit. There was definitely a sense of 'we could be doing this', even 'we should be doing this'."

Art world exhibitions are obviously very different from demoscene competitions, and neither Smash nor EvilPaul had to prove that the production is indeed running in realtime. "You just had to send a video," explains Smash. "It does work realtime though!" he adds with a laugh. EvilPaul explains in more detail that it was left fairly open: "As long as you could put it up on Vimeo, they were happy. It was interesting that no-one else seemed to do anything really exciting or fresh." Smash closes the subject: "About half the others were non-realtime Aftereffects jobs, it was allowed." Participating in the competition was a very straightforward affair, says Smash: "You just sent in the video as a vimeo link and that's it." The event was organized by a group called OneDotZero. They also organized some free workshop/screening events at the V&A that both Smash and EvilPaul attended. "I'd be interested in being more involved with them but, as Smash says, they don't seem very communicative, which has put me off just speculatively contacting them," elaborates EvilPaul. "They seemed focused on art school graduates - which I am most definetly not. I really should just email them though."

| "You just sent in the video as a Vimeo link and that's it" |

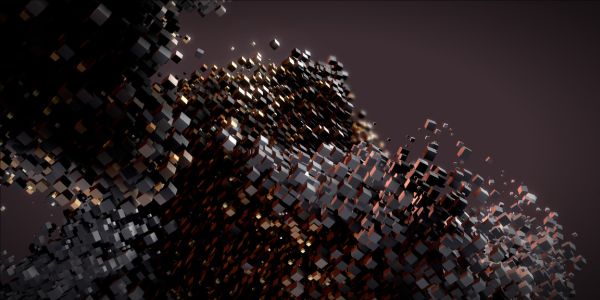

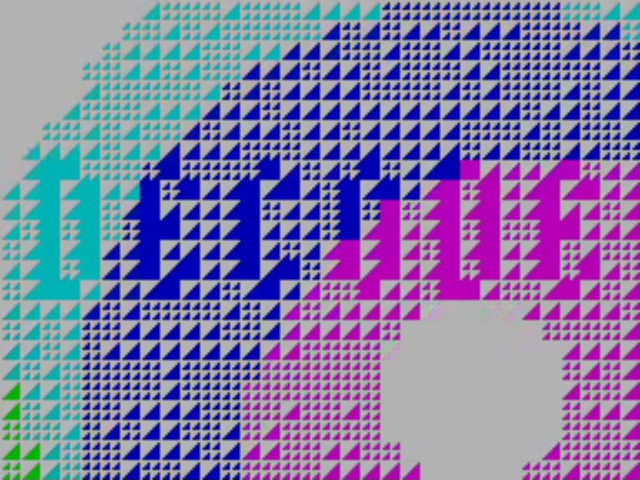

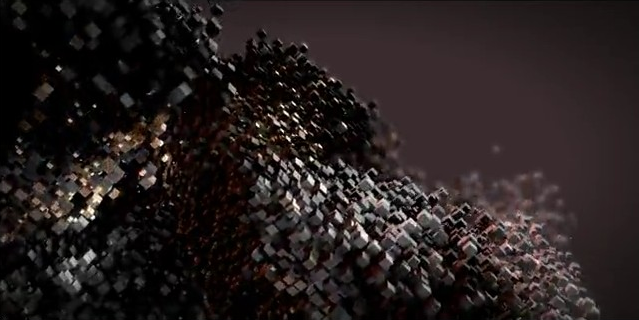

Inquisitively, ZINE goes further into the question of just how different the work on these pieces was compared to working on a normal demoscene productions. "It's a totally different audience," explains Smash. "What people want from a demo is like a 5 minute piece of entertainment - some form of story/theme, multiple parts are almost demanded, definitely multiple ideas and content, some big effects, logos, greets.. there's a huge history there which has formed what a demo 'is'. You can go against that of course, and we have in the past, but there's definitely such a thing as a demo-style demoscene demo. Even some of our pretty un-demo pieces - like Agenda Circling Forth - still follow the rough plot; multi-part, logos, some 'wow' moments, a story arc etc. It's the way people watch demos - in competitions, they want those 'wow'-moments. At home they sit in front of their PC just to watch that demo and they want to be entertained. Perhaps this isn't a good thing, though. Outside the scene it's totally different. People want something like a minute long piece that has one idea, one concept, well formed and followed through. If you do multiple parts and many ideas, or do something too long it's actually a bad thing. It's hard for people to follow and understand. I guess it's because people watch the thing in a different context. A dedicated demoscener might sit down to watch an 8 minute demo in a democompo and give it his full attention. But in the 'real world' people have short attention spans - they need to be grabbed instantly and only demanded to watch for a short while. The other thing is we spend a lot of time in demo or game gfx chasing realism and so on. In this other world people would watch a proper render or a film to see realism. They don't want to see a realistic animated character with nice lighting. They want to see something done in code that celebrates being done with code - like tons of cubes, animated in a nice way, that you would never want to do offline by hand. In this world, being coded has to be for a reason; you want to make it look coded. In the demoscene it's the only choice so people chase realism. That's a huge difference - what is 'cool' is completely different."

EvilPaul sits listening intently, and nods his head: "Agree with all of that. The demoscene really is a different world and it's very hard to communicate the 'context' to non-sceners, which makes it difficult to get our work across to a different audience. Some stuff definitely crosses over - you can appreciate Lifeforce or Frameranger even if you don't know or care that it's realtime, and, say, PWP's stuff is understood because the context is so obvious."

| "People want something like a minute long piece that has one idea, one concept, well formed and followed through" |

As far as after-the-matter recognition goes, the duo didn't anticipate much. There were plans to display some of the better contributions on the London Underground, but it appears that the pieces have yet to appear. Smash: "It never happened as far as I know - because I submitted far too late, in traditional demoscene style." There was some mainstream recognition though, Smash's piece was featured in the Metro newspaper. "It was cool because some of my 'real life' friends could see it and finally understand what I do in some form that's acceptable and digestable. You dont have to sit there explaining what a demo is or trying to make it sound not geeky; you just say 'here, see this article'."

| "I want to do smaller, more focused projects" |

In closing, the two are enthusiastic about pursuing similar work in the future. We ask if any concrete plans exist at this time, and Smash replies: "Maybe not specific, but the main thing is I want to do smaller, more focused projects and also do more that's cool outside the demoscene. Demos are very hard and draining and with relatively little return - who really cares about a compo these days? It's fun for sure, but I dont know how long I can go on repeating the same thing over and over - doing a demo for Breakpoint (or whatever is replacing it), a demo for Assembly, year in year out. I need to evolve. I'm doing some stuff in the world of interactive installations, also some little amateur music video projects, but it's all small stuff and early days." EvilPaul does not differ: "Again, I'd agree with that. I'm currently looking at VJ stuff and thinking hard about art installation pieces because I too feel the need to evolve. It's also sad but true that demos don't pay the bills. As I get older and family takes more of my time (of course I wouldn't want to change this!) then it gets harder to justify spending so much time and money on demoscene stuff. I think the only way that I'll be able to continue doing what I love in the long term is to evolve it into something that pays. The worst thing though is that I keep finding demoscene projects that I want to do..."

Looking back, Smash wonders about the experience of participating; "It's all pros, I guess. It got exposure, it was easy to do and it was fun. The whole thing took about 2-3 days max, was quick to edit etc and it did really well - good exposure online and in the Metro. It also really helped to build up 'non-scene' contacts. There's a whole other scene out there, people doing stuff in processing etc. It's massive and it's really big in the commerical world too - open frameworks, interactive installations. The fact is, that in terms of technical aspects, realtime gfx, etc, we destroy them. We're miles ahead. But we have something to learn from them too in terms of making our work accessible, celebrating being coded, and not chasing realism - picking our battles basically."

Go back to articlelist |

|

|

|